A GRAND EXHIBITION AT NATIONAL MUSEUM NOT ONLY REVERES AND ADORES GANGA – AS A RIVER AND A GODDESS – BUT ALSO LIBERATES IT FROM NARROW COMMUNAL FRAMEWORKS EXPLORING TRADITIONS, ARTS AND CULTURES OF INDIA, FINDS OUT

RASHME SEHGAL

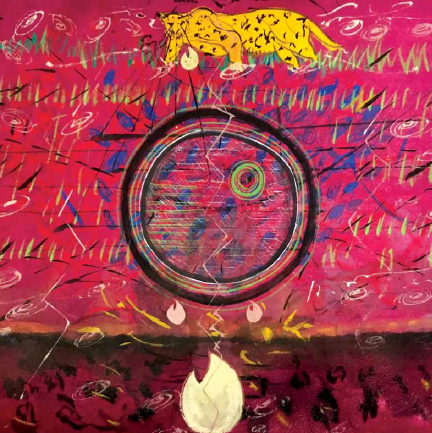

No river is as beautiful and historical as the Ganga. Successive civilizations have been built around this iconic river which is a source of wonder across the globe. Classical accounts depict her in reverential tones in countries across the globe, including Italy, Greece, Ceylon, Cambodia, Thailand and Indonesia. So much so that the Fountain of the Four Rivers in the Piazza Navona in Rome built in 1651 includes River Ganges as one of the four greatest rivers in the world, but extraordinarily, the Italians chose to depict her as a bearded male similar to the famous frescoes depicting God in the Sistine Chapel painted by Michaelangelo. While the Ganga may have a male physiognomy in the western hemisphere, in India and the Far East, she is depicted as a sensuous and playful woman, a consort of gods and a distributor of wealth. One of the most beautiful idols on display at the National Museum where this exhibition titled Ganga: River of Life & Eternity is being held, is a life-size image of Ganga taken from a Shaivite temple in Ahichchhetra in Uttar Pradesh. She is shown as a bejewelled goddess standing on her vahana (vehicle), which is the Makara (crocodile) representing untamed energy. This exhibition curated by the Boston-based Shakeel Hossain, shows the river through her many histories, traditions, arts and cultures right up to the modern age. This collection becomes all the more significant because Ganga was recently declared a living entity by the National Green Tribunal with, all the fundamental rights that an individual is entitled to. But the fact that the river is a living entity is something our elders understood much before us. The importance they imbued to her can be gauged from the fact that she is seen to a celestial being whose waters were prized nectar for the gods many of whom fought pitched battles for the ownership of this nectar. Hossain, whose passion for the river can be seen from the care and patience taken to collect this variety of rare artefacts and paintings, correctly points out that this exhibition on the Ganga provided an opportunity to present Indian creative expression through one icon. No wonder the viewer on entering the gallery is introduced to 1,000 names of Ganga woven around different mythological stories. There is Vishnupadi, originating from the belief that Ganga emanated from the lotus feet of Vishnu. Another story highlights the mythical cosmic egg, which is the source of all creation. The Ganga remains very much part of this cosmic creation, integral to Hindu mythology from the time of the very inception of the universe. The tale of the golden egg (Hiranyagarbha Sukta) goes back to the Rig Veda, which describes the origin of the earth from a cosmic egg with water significantly being the source of wellbeing for all mankind. A quote from the Rig Veda highlights the significance of the Ganga followed by a large panel depicting how the Warli tribals see the river in association with all five elements. This large Warli painting is stunning in its sheer exuberance. It shows a tribal man dancing with joy. He is wearing a long scarf with the Ganga River forming a sheet of water in the backdrop, sea gulls fly around him with the sliver of a silvery moon forming the backdrop. The man is surrounded by an ocean of water in which fish are seen riding these waters. The painting is done in silver against a navy-blue backdrop which allows it to make a spectacular statement of how intrinsically mankind is linked to his environment. The importance of water can be gauged from another apocryphal tale on how the capture of the celestial rivers resulted in a drought on heaven and earth. Indra was forced to capture Vitra in order to allow the rivers to descend from the heavens in order to flow back to earth. The gallery has a number of artefacts woven around Ganga’s descent from heaven and also how she is closely linked to the three divinities of Saraswati, Lakshmi and Parvati. There is a beautiful miniature on display where Krishna is shown mollifying Radha who is jealous of his closeness to Ganga. Even as he is mollifying her, Ganga can be seen hiding under the foot of Krishna. A Jain Cosmo gram projects the river as sacred, even as her very birth remains a subject of debate. She is shown coming out of Vishnu. Others insist Ganga is the daughter of Himavat and Mena, and the sister of Parvati. Another belief highlights how her descent to earth is linked to Vishnu in the Trivikrama form, when he crossed the three worlds and burst the heaven in his second step, causing Ganga to fall into this universe. The most popular belief is of course how Shiva brought her down to earth with his locks helping to slow down the force of her flow. Hossain has used many artefacts from the collection of the National Museum. There is one gem emphasising the Trivakarma avatar of Vishnu in a sculpture, and another of Brahma holding a kamandal with Ganga water. According to Indian cosmology, the Ganga flows in heaven, earth and the underworld. Ganga has also been shown to be the consort of Shiva, the foster mother of Kartikeya, and the wife of King Shantanu and mother of their son Bhishma, who is shown dying on a bed of arrows in a miniature from the National Museum collection.The miniature depicts how Bhishma is lying on a bed of arrows waiting for the sun to enter its northern equinox so he can take his leave from the earth. When Bhishma is thirsty, Arjun shoots an arrow into the ground and the Ganga comes gushing forth from the earth at the exact spot where the arrow has entered the earth. This is another form of mother Ganga who has come to quench the thirst of her dying son. The Ganga has been depicted through the ages in the Stone age, the Harappan Age, the Vedic Age, the Buddhist Age, the Gupta period and then in the reign of the Chalukyas, Cholas and Palas, the Slave Dynasty, the Khaljis and Tughlaqs, the Lodhis and then through the Mughal dynasty. In fact, some of the most elegant works on the Ganga have been depictions in the miniature style. Some of these works have been shown at the exhibition. Works in the Gupta period show her as the goddess of purity, an account in the Ain-i-Akbari describes Akbar’s love for Ganga Jal, which was carried with him wherever he went. Ganga remains equally important in contemporary times. There are panels showing her importance during the Kumbh Mela, other panels depict Ganga aarti at the ghats of Banaras. There is another rare gem on display of a pilgrimage map of Banaras from the 17th century, when the Varuna and Assi rivers flowed into the ghats while the Ganga continued her northward journey past the ghats culminating into the Bay of Bengal. The artefacts on the Ganga belong to the syncretic tradition of India. One section has been devoted to how tazias made by Muslim artisans who were followers of Imam Hasan-al-Ansari. These are immersed in the waters of the Ganga.

The Nawabs in Mushidabad followed a tradition of building rafts or beras. These rafts were shaped like crocodiles, the vehicle of the Ganga, which were used to make offerings to the river. There are a number of maps on display along with film posters from Hindi cinema. There is a lovely poster of Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai and Gangaajal. Hossain quite rightly believes the river has been appropriated by Bollywood with great commercial success. The last part of the exhibition is the most poignant because there is no doubt that the Ganga is facing impending death with thousands of tonnes of pollutants and sewage being dumped into her through her long journey from Gaumukh to the Bay of Bengal. It is now up to the people of India to save this precious heritage. Whether they will is another issue completely.

" >

" >

" >

" >