Even as he feels lonely in the present times of a new normal, acclaimed artist Riyas Komu challenges himself to remain alert and active through his art, says Neelam Gupta

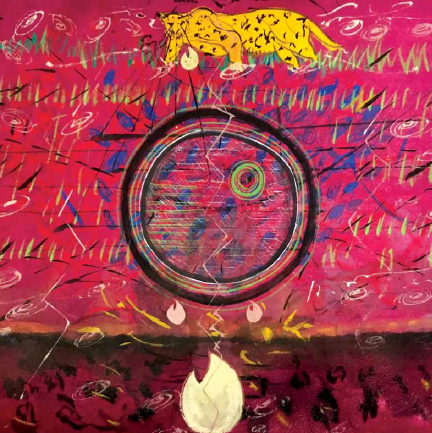

A master storyteller and one of the most influential artists active today, Riyas Komu began life studying literature when he actually wanted to pursue textile design. “My parents wanted me to become a doctor, but for bachelors I had to switch to English literature as I didn’t score enough for science,” says the Mumbai-based artist, curator and educationist, who as a child was obsessed with becoming a footballer. For Komu, who was born in Thrissur, Kerala, art is a medium for social commentary on the situations the world is facing today. The critically acclaimed multi-media artist, whose works depict aesthetically brilliant imagery and a strong personal narrative, believes that internal conflicts and political events offer a chance to reflect upon our own presumptions and values through which we relate to the world at large. “Good art is always true to its political times,” says Komu, who has successfully explored the shared histories and colonial encounters of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan and Maldives through his Young Subcontinent Project.

A master storyteller and one of the most influential artists active today, Riyas Komu began life studying literature when he actually wanted to pursue textile design. “My parents wanted me to become a doctor, but for bachelors I had to switch to English literature as I didn’t score enough for science,” says the Mumbai-based artist, curator and educationist, who as a child was obsessed with becoming a footballer. For Komu, who was born in Thrissur, Kerala, art is a medium for social commentary on the situations the world is facing today. The critically acclaimed multi-media artist, whose works depict aesthetically brilliant imagery and a strong personal narrative, believes that internal conflicts and political events offer a chance to reflect upon our own presumptions and values through which we relate to the world at large. “Good art is always true to its political times,” says Komu, who has successfully explored the shared histories and colonial encounters of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan and Maldives through his Young Subcontinent Project.

“Even though I used to feel very lonely, a feeling I get even now, I have challenged myself to remain alert and active through making art, politically and aesthetically.”

His artistic practice has become known for its narrative dimensions, combining film, photography, sculpture, installations and painting in the service of social and political critique. Most of his artworks are inspired by the social movements and political events of current times, speculating issues like violence, dispute or displacement. In his own words, “As a student, I moved away from textile design and started learning visual art, beyond that the chaos and the human suffering the city (Mumbai) went through after 1992 prompted me to think of art as a site to learn and express secular humanistic beliefs through my expressions and since then has been the basic conceptual framework of my practice.” With memories playing a hugely significant factor in his projects, Komu’s work conjures elements of curiosity. It addresses a sense of identity – aesthetics in which we, as viewers, can compellingly indulge. “The hardships I went through; missing life with my old parents, inspired me to new ideas of making art and new sites of learning,” he says, adding, “My experiences from my travels have contributed in a big way to the making of my art. I gained confidence to do art through my journeys and visits to museums and cultural institutions all across the world,” says the artist, who was always interested in watching television news. “Those early figurative images in my works came from television images and international news,” he informs. “Later, I started focusing on oil paintings and started doing portraits of young migrants into the city. I was always interested in large scale paintings and the single layer treatments that I developed are the key to those works.” Co-founder and Secretary of the Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF), Komu was one of two artists from India to be selected by curator Robert Storr for the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007 and he represented the Iranian Pavilion at Venice Biennale in 2015. In this interview with Art Soul Life, Komu speaks about life, work, his love for textile and how he tries to understand the idea of making through many political and cultural symbolism connected with “weaving” our nation has experienced.

You landed in Mumbai in 1992 to study textile design, but switched to Fine Arts. Any particular reason?

I grew up in a large family among seven brothers and two sisters. My parents gave me an emotionally expensive ticket to Mumbai as I wanted to pursue textile design, a passion I still carry along. As a child my obsession was to become a footballer. When I was in college my parents wanted me to become a doctor but for bachelors, I had to switch to English literature as I didn’t score enough for science. In 1992, while I was doing my BA, my brother Ibrahim insisted that I pursue my passion, upon which I secured admission in JJ School of art and left Kerala. I started enjoying my longest campus life ever by immersing myself in multidisciplinary activities as part of the academics. Parallely, beyond my recognition of it, the city was splitting apart. As you know, 1992 was a crucial year in Indian history in which we saw the emergence of communal politics, hatred, polarisation, giving a big jolt to the democratic fabric of our society. The coming apart of the city marked my life too, as I grew up in Kerala in a plural atmosphere and with political constitutional values. When I started living in Mumbai my experiences of growing up with hard working parents, who believed in the history of social action became an ideal and virtue to hold on to. Easily, Mumbai became my new home in every sense; crowded local trains, aspiring migrants, growing art world, busy people, music and cinema, and the city that never slept started growing in me. As a student, I moved away from textile design and started learning visual art, beyond that the chaos and the human suffering the city went through after 1992 prompted me to think of art as a site to learn and express secular humanistic beliefs through my expressions and since then has been the basic conceptual framework of my practice. That humble beginning in response to the time, a challenging decision, I took in isolation which gave me a new identity to move forward as an artist. But I still maintain my love for textile and keep trying to understand the idea of making through many political and cultural symbolism connected with “weaving” our nation has experienced.

When and how did you get interested in art and art curation?

Believe, interest in curation was part of my evolution as an artist. Initially, I worked on many major projects as an assistant in curating, logistics and administration, which gave me a lot of confidence in working with people on large scale sites. My large studio supported by a team of skilled carpenters, carvers and other technical assistants gave me a sense of ease to work and I developed a great belonging with the community. It was a period I worked like mad and produced many works and did international projects. I feel proud that I could represent the country at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and my participation was an eye opener in understanding the relevance of political art. It also offered me a big opportunity to showcase my work in one of the biggest international projects along with major artists. Curation for me is a site to dissent along with like-minded artists and youngsters. I cherish the co-curating of the first edition of Kochi-Muziris Biennale as an act of political and cultural importance in building an ecosystem engaging with history, people and art. My long engagement with the well-researched Young Subcontinent project, which I began conceptualising in 2015, is the best experience I ever had in the act of curation and travel and exhibition making.

Your photographic or hyper realistic style is very popular. What do you have to say?

Painting is one of my practices where I find a sense of reflectiveness, especially at times when it provides me with a feeling of compassion. I think continuous working and practising seeing is the most important thing for an artist to develop their perspectives, skill and aesthetics. My experiences from my travels have contributed in a big way to the making of my art. I gained confidence to do art through my journeys and visits to museums and cultural institutions all across the world. I began to engage with mediatic-realism as I was always interested in watching television news. Those early figurative images in my works came from television images and international news. Later, I started focusing on oil paintings and started doing portraits of young migrants into the city. I was always interested in large scale paintings and the single layer treatments that I developed are the key to those works. As artists when we are working upon the material consciously, it happens that we are simultaneously worked upon by the texture of the materials that takes us to the realm of the past; memories, dreams and all that goes with them. The physical aspect of making art and the presentation of it as a work travel through many layers of time, space and memory.

Some of the major motifs in your work have been migration, displacement and exile. Why theseparticular topics of interest?

As I mentioned earlier my shift to painting was a decision that evolved out of the historical political site and the moment I was in. In fact, if you notice the works I produced since then you will see a gradual process of moving into diverse issues around displacement and exile. My early shows spoke on religion as a site of conflict. The polarising nature of religion was very much the theme of my 2005 solo titled Faith Accompli. The ‘Left Legs’ project with the Iraqi football team was a project on exile, longings and it was deeper research in understanding the resilient nature of humans. In ‘Watching the Other World Spirits from the Garden of Babylon,’ a large installation I showed as part of my solo show in Berlin titled ‘Related List’ is a stark reminder of the war and occupation. The ‘Designated March by a Petro Angel’ is a series I showed at the Venice Biennale that speaks about religious fundamentalism, patriarchy, alienation and sufferings of women in social spaces. I published a tabloid called Brick, which is intended to explore deeper into such sites through photographic research supported by statistics and analysis.

What message do you want to convey with your works that are inspired by social conflicts and political movements?

When organised hatred has upstaged the new normal, art carries the meaning and relevance of its practice. In a time where everything is in chaos, I have kept myself away from mediocrity and wanted my practice as a site to engage in conversations. According to me, when I shared the idea of doing a Biennale with the Education and Cultural minister of Kerala, it was in a way one of the most important political acts I have done so far in my career as an artist. The idea was shared with a receptive political mind and I feel proud.

Artists never work in isolation; their process of work is interspersed by acts of people on the street and elsewhere. In a country like India where the density is so thick that one body cannot be separated from the other, a mere gesture of walking on the streets appears as a collective search for meaning. There has always been a social movement behind art; the secular public sphere created by art with the energy of social movements is a very important gesture towards making art in the sense of a community.

Other than promoting the local artists, what was the idea behind Kochi-Muziris Biennale?

Biennale is a site of dissent, politically and culturally and it should remain one. It was introduced in Kochi with a larger aim of discussing art history, politics, making and thinking and emerging social trends in the world. It did the much-needed cultural acupuncture and the system has benefited immensely out of it. It rejuvenated a much needed ecosystem from all perspectives. The Biennale changed the perception about contemporary art practice among people, empowered young artists, educated the aspirants and connected children with art and its immense emancipatory potential.

Another important aspect worth emphasising is that it gave unimaginable possibilities to local art and increased the confidence among youngsters, which I think is getting noticed more and more. The global perspectives and emerging discourses that the biennale brought to the shores of Kerala created a new art route which celebrated local cultures with radically refreshed memories of arrivals and departures. After all, the art world got a site like Kochi to come together at a place where many communities live together and speak different languages. Most importantly, a project supported by a politically, culturally and socially active state like Kerala is the backbone of the Biennale.

Education via the pathways of art is a very important element of knowing oneself and the community. The idea of having a biennale of our own was a collective search for meaning on the one hand, and working out the secular and political public sphere on the other. We need institutions that look after the passions of many, not the interests of powerful elites.

What is your view on the international art fairs like Venice Biennale and Indian artists’ participation in these fairs?

Biennale are sites of experiments and imagines art practice beyond the confines of galleries and museums. As an artist who participated in Venice Biennale in 2007 curated by Robert Storr, I feel biennales and Triennale’s offer a platform to take our discourses to a community that engages the most with art of the time. It helps in doing survey projects. Biennales are the sites that showcase emerging concerns and present curatorial experiments; it is also an international gathering of scholars, historians, curators, artists, students and art lovers from across the world. A nation which can host a biennale grows in confidence among the world and it will bring opportunities. Indian artists have started getting more opportunities in international projects and they also have started curating many of them at important sites, globally. It is sad to add that we don’t have a pavilion in Venice this year and it shows how divided the art world is and it is definitely not a good sign for the future of Indian art.

What is your take on multimedia art and video installations?

I have gained confidence in making art by probing into all kinds of experimental sites that provide and provoke you with larger possibilities. Art has no limitations but personally feel its language has to work towards its maturity in whatever form it assumes. I work a lot with different materials and it comes as a basic requirement or as a material to engage in conversation with our time. For instance, cinema is one medium that has been using all the possibilities offered by existing and emerging art forms, sounds, textures and technology. In multimedia art projects that incorporate cinema with its full strength and its new age digital attributes have in many ways enhanced the aesthetic and physical and emotional experience of art on many levels. Today, as technology is inseparable from our skins, young artists are at the forefront of these practices. They look at many layers, textures, diversions, pitfalls, spatial coordinates and temporal visions within the cinematic time to explore their own place and self in a community of shifting and altering populations. The other perspective is that the dominant medium of audio-visual method has been co-opted by surveillance and state agencies to limit the movements of the people and people know they are being watched, their spaces are being taken over so much so that they remain visual prisoners without there being a wall. The importance of this medium lies in the transformation of this space of social gaze into a subversive art practice.

What is the future of art considering the fact that NFT is taking off in a big way?

These are outcomes of human innovations especially in the face of an economic crisis, but this revolutionary method demands transparency, accountability and should empower its users. In this case, I hope, it will definitely be much more democratic in its use and application, and for artists it will offer a systemic economic platform as it moves further from site to site. We all know that technologies of communication and transaction will keep emerging with new trends even further.

How will art shape up in a world that is heading towards the metaverse?

I think we should not worry much about the fate of art in a collapsing world. We need to ask the question in reverse; whether we have a future without art, this is one, the other important thing to note is that we should not be thinking that art ceases to exist when everything falls. The reverse is true, the art goes on, into the future when everything falls apart. There cannot be art without a future and the reverse. Art and time are intimately connected. That is why every event in history has been followed by art and to a certain extent it is also true that art practices have created historical and social transformations in the ways of seeing.

" >

" >

" >

" >