Much like the upper caste tradition of Kachni and Bharni Mithila paintings, the Dalits have for decades been decorating the walls of their homes with an alternate art form called Godna TEXT: TEAM ART SOUL LIFE

We have all heard of Madhubani or Mithila art which is said to have developed in the ancient city of Mithila, the birthplace of Sita, daughter of King Janak. It is said that the Mithila paintings were commissioned by the king to commemorate the marriage of his daughter to Lord Rama of Ayodhya. It was recognised as kulin art, or art of the pure castes.Traditionally, these paintings were done by Brahmin and Kayastha women. Ganga Devi, a Kayastha, and Sita Devi, a Brahmin were the two pioneers of Mithila paintings on paper. While Ganga excelled at kanchi or line paintings, Sita Devi developed the bharni style or “filled” associated with the Brahmin community. However, there exists an alternate art form by marginalised communities that seldom comes into limelight. Much like the upper caste tradition of Kachni and Bharni Mithila paintings, the Dalits have for decades been decorating the walls of their homes, which looks similar to Alpana (floor) paintings, but are different in motifs used, which is stylistically typical to the Dalits, namely the Dusadh community in the village of Jitwarpur in Bihar. Much like the upper caste tradition of Kachni and Bharni Mithila paintings, the Dusadhs castes have, for decades, been decorating the walls of their homes for rituals. However, because of their lower caste status, they were not allowed to showcase the divine in their artform. Thus, they found inspiration in geometric forms and flora-fauna surrounding the village.

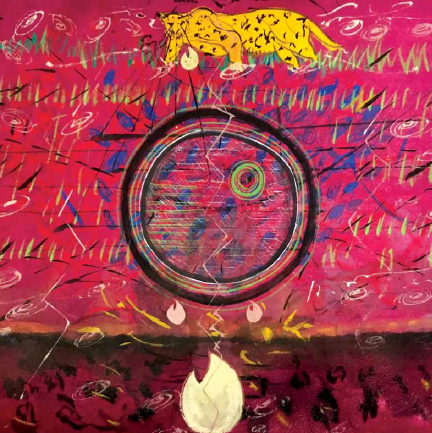

Among the many decorative styles from these castes was the Godna style, inspired from the Godna (tattoo) art practised by the Nattin (Gypsy) women. Their visual language includes parallel lines and concentric circles containing floral motifs and the human form. More recently, local heroes are drawn in this style of painting. Raja Salhesh’s oral narratives and paintings, for example, are used as a symbol of resistance against upper-caste politics. He was a military man, who is now revered as a king, remembered for standing up against the discrimination of Dusadhs. Since 1972, even the Brahmins and Kayasthas have appropriated the style.

The credit to Dalit inclusion in Mithila paintings goes to a German anthropologist, Erika Moser. Works on paper painted by low-caste women appeared for the first time during the 1970s when Moser visited the Madhubani district to study and film the crafts and rituals of the Dusadh. Moser encouraged the Dusadh women to paint on paper with the aim of generating extra income. The Dusadh women, encouraged by Moser, began to take inspiration from their own oral, cosmological and aesthetic traditions. When Moser, also a film-maker and social activist, first started persuading the impoverished Dusadh community to paint, the women, caught up in hard physical work, expressed inability to do so as they had little awareness of the stories of Hindu deities usually depicted in Mithila paintings. A guiding hand from their high-caste counterparts seemed difficult owing to social differences. This is where motivation and skill-specific advisory, from the likes of Moser and American anthropologist Raymond Lee Owens, came in handy. The result was that Dusadhs started capturing their oral history — such as the chronicles of local deity Raja Salhesa — and depictions of their primary god Rahu in their paintings, which were carried out using a bamboo pen and black ink. This style was adopted by a large number of Dusadh women and evolved over time to include the use of plant designed colour schemes based on flowers, leaves, barks, fruits. They developed three styles and techniques that are specific to them.The first was initiated by Chano Devi (1938- 2010), a National Awardee, and takes tattoos as its stimulus.

This style is now known by the name godhana (godna means tattoo). These paintings are largely composed of lines, concentric circles, and circles filled with motifs taken from the flora and fauna. During this time, Mumbaibased artist Bhaskar Kulkarni, who assisted cultural activist Pupul Jayakar to revive many traditional Indian arts, including Warli, saw Chano’s work and bought a lot of her artworks besides encouraging her to work more. Chano and her husband Rodi Paswan in their attempts to popularise and mainstream this art form trained several artists. This style is easily recognisable by its sepia background that is attained through applying cow dung diluted water on paper. Chano also started to experiment with natural colours in order to create a more distinctive style. These colours later became the main identifier of Dalit Godna paintings, as other painters too started to abandon the use of Holi colours in favour of those made from cowdung base, leaves, flowers, vegetables, barks, and roots. Godna painting remains a relatively lesser-known form as compared to kachhni and Mithila paintings. Dalit artisans practicing this art form are still struggling to get a decent income in markets. The art and its history has not yet received the appreciation and recognition that it should. Meanwhile, a group of locals from Bastar in Chhattisgarh has taken up the task of reviving the region’s age-old ‘Godna’ art form, which they believe is the only ornament that remains with them even after death. This primitive artistry, known for traditional designs like the bow and arrow and bison horn headgear, is waning in the fast-changing world as people are more attracted towards the modern tattoo designs. A catalogue of the traditional Godna patterns and stories behind them is also being prepared to conserve this art form, a prominent tattoo artist from the state said.

" >

" >

" >

" >