An art odyssey, Sixteen-III, with sixteen artists aims for optimism and inner joy say’s Prof Dr Amargeet Chandok

A group exhibition, Sixteen-III, of paintings, drawings, ceramics, graphics and sculptures by sixteen artists, was held at the Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre, Delhi from September 29 to October 3, 2023. Akin to a beautiful bouquet, a variety of techniques and mediums were used. Altogether they created a colourful kaleidoscope of diverse art. For briefs of the sixteen artists and their art, read on. Alpana Mahajan, a contemporary Indian artist, works with various mediums such as acrylic, oil, watercolour, and mixed media. Alpana uses bright and contrasting colours to create a vibrant effect. She draws inspiration from nature, spirituality, and mythology. Her style is influenced by the folk art of Alpana or Alpona, which is a traditional form of floor and wall paintings by women of Bengal. Alpona consists of coloured motifs, patterns, and symbols that are painted with rice flour on religious occasions and festivities. The motifs relate to specific deities, festivals, or seasons. Alpana incorporates some of these elements in her paintings. Her paintings celebrate India’s rich heritage while representing the mundane daily activities.

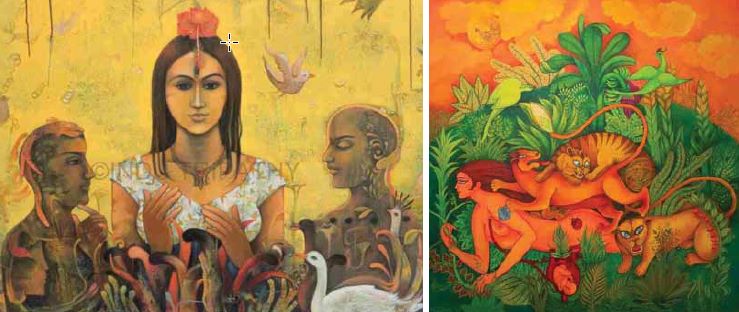

Angelica Basak, founder of Artify Studio, is a contemporary Indian artist who works with oil, acrylic, watercolour and digital media for her paintings and sketching. She likes to paint portraits, animals, landscapes, abstract and nature. She uses a variety of techniques, such as blending, shading, and highlighting, to create realistic and detailed effects. She also adds elements of fantasy and the quaint to her paintings, such as butterflies, flowers, and stars. Her art style is influenced by the Indian culture and heritage, Raja Ravi Varma’s works as well as those of other artists, such as, Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo, Dali, Picasso, amongst others. Her works are expressive, emotive, surreal and diverse. Arup Kumar Biswas is a contemporary Indian artist who is a painter and a sculptor. He works with acrylic, oil, watercolour, charcoal and clay. He creates abstract and semi-abstract paintings that explore the themes of nature, spirituality, and human emotions. He uses a variety of colours, shapes, and textures to create a visual harmony and contrast. He also adds elements of symbolism and surrealism to his paintings, such as birds, flowers, and faces. His art style is influenced by the Indian culture and heritage, Gurudev (Rabindranath Tagore), Jamini Roy, Nandalal Bose, as well as by the works of artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Picasso. He has used various representational elements like plastic bottles, disposable plates, small rings, water taps, etc. (i.e., objects most commonly used in our homes). His objective is to highlight the fleeting nature of time – and that, it is not happening somewhere in space or in isolation – but it is here and now.

Ashwani Kumar Prithviwasi is a contemporary Indian artist who is also the founder and principal of Delhi Collage of Arts. He works with various mediums such as oil, acrylic, watercolour, and charcoal. He creates realistic and semi-realistic paintings that depict the beauty and diversity of Indian culture, especially the rural life, festivals, and traditions. He also draws inspiration from nature, spirituality, and human emotions. His style is influenced by the folk art of Alpana. Ashwani incorporates some of these elements in his paintings, such as lotus flowers, conch shells, owls, and geometric designs. He also uses bright and contrasting colours to create a lively and dynamic effect. His paintings are a celebration of the rich and diverse heritage of India.

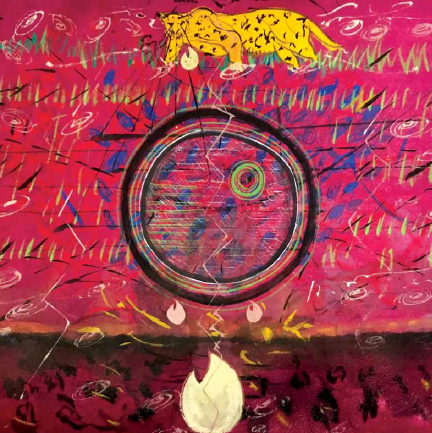

Dr Deepak Kumar Ambuj is a contemporary Indian artist and has a Ph.D. in Fine Arts. He has won many awards and accolades for his works. He is known for his abstract and figurative paintings that explore themes such as identity, nature, culture, and spirituality. His art style is influenced by Indian folk art, expressionism, and surrealism. He uses vibrant colours, geometric shapes and symbolic elements to create dynamic compositions.

Faiyyaz Rashid Khan is a painter and educator. He uses a variety of techniques, such as realism, impressionism, expressionism, and abstraction to create his unique art work. Figures and forms are intertwined to great effect along with the bestial and human forms showing associations with surroundings and creating the surreal. He experiments with oil paintings, watercolour, acrylic, charcoal, soft pastel, and portrait paintings and drawings. His themes are based on nature, culture and spirituality. He also incorporates elements of Indian folk art, such as Warli and Madhubani in some of his works.

Hem Jyotika is an Indian artist who works with acrylic on paper. Her abstract paintings are inspired by nature, spirituality, and human emotions. Her art style is characterized by vibrant colours, fluid shapes, and intricate patterns. She uses a technique called the silk thread, which involves applying thin layers of paint with a brush or a needle to create a textured effect. She also incorporates elements of Indian folk art, such as mandalas, paisleys, and flowers. Her ‘Divine Art’ collection explores the themes of nature, spirituality, and human emotions. Her works evoke all shades of emotions. Apart from painting, she has directed several documentary films including the critically acclaimed ‘The Female Nude’ that was adjudged as the best film on social issues at the 56th National Film award Indu Tripathi works mainly with acrylic on canvas but also loves watercolours for their transparency and spontaneity. Her works are inspired by her love for nature and spirituality.

She is known for her figurative works which are often described as ‘lyrical’. Her art symbolism and adroit use of contrast, texture and composition are hallmarks of her work. Lalit Bhartiya is a self-taught artist (painter, photographer, musician and a litterateur). His love for realism, shapes much of his work. He mainly uses acrylic on canvas. He also uses poster colour on silk. His body of work also includes realistic paintings with dry pastels and water, poster, stone, oil and acrylic colours.

Lalit Mohan Pant is also the curator of this show. He works with charcoal on paper. His themes span across abstract figurative, abstract landscapes and nature. He tries to capture the invisible connections and interactions amongst nature, human emotions and spirituality. Many of his works have found their rightful place in private, corporate, museum, gallery and government collections. He draws his inspiration from nature and strongly feels a deep respect for it as he says that nature gives in abundance but also takes everything back at a slightest whim.

Maitreyi Nandi mainly works with acrylic on canvas. She also works with oil, watercolour and mixed media. Her style is quite distinctive and is shaped by her love for nature, spirituality and Bengali culture. Her strokes are expressive and the hues vibrant. Other than painting, she works for and espouses women empowerment through NGOs. Pankaj Saroj is an Indian artist who works with various mediums such as oil, acrylic, watercolour, and mixed media. He paints colourful landscapes, flowers, birds, and human figures in a semi-abstract manner. Many of his works are influenced by his childhood memories and later travelling through stunning mountains capes. Through his works, he seeks to capture the tranquillity and harmony that abounds in nature.

Rajesh Kumar Tanwar is an Indian artist who works mainly with acrylic on canvas. His works contain geometric shapes and patterns in abundance, the themes include spirituality, about emotions (for example, happiness) and nature (for example, colourful birds on abstract backgrounds), and landscapes. He has received several awards and recognition for his works. Ram Sanjeevan is a noted sculptor. His ‘Apple Series’ of sculptures are dedicated to return of normalcy, peace and humanity in the valley of Kashmir.

Prof (Dr) Sanjeev Kumar is an Indian sculptor. Prof Sanjeev Kumar is presently Principal, College of Art, Delhi. He is also working in ceramics and uses various mediums for his artistic expression. He works mainly on stone and bronze. He also uses ceramics, terracotta and fiberglass. He is known to experiment with different patina, finishes and textures. His art style is primarily influenced by Puri and Mathura styles. His works are often based on Hindu Gods and Goddesses.

Shampa Bhattacharjee is an Indian painter who works with acrylic on canvas. She is a self-taught artist. Her art style is unique and original and doesn’t follow any particular school of art. Her paintings express her personal views on life, nature, spirituality, and human emotions. She uses vibrant colours, expressive strokes, and symbolic elements to create her works. Her works are sought after by collectors and art lovers. She has also donated some of her paintings, the proceeds of which have been used for those affected by COVID-19 and the Amphan cyclone. Altogether the works exude hope, positivity and are inspirational.

About Dr Amargeet Chandok

Dr (Mrs) Amargeet Chandok is Head of the Department of Painting at the College of Art, New Delhi. She holds a PhD in Fine Art. A recipient of the Priyadarshini Indira Gandhi Award for Lifetime Achievement (2001), she has to her credit the world record for the biggest painting of Mount Everest signed by Sir Edmund Hillary. She has been conferred with various award namely:

- Indian Icon Award 2022, on the occasion of 73rd Republic Day Celebrations

- Chairman of The All-India Sikh Conference – 1996

- WCCI- Secretariat, University of Cincinnati, USA- 1995

- Dr. Karan Singh, Minister Culture- 1992

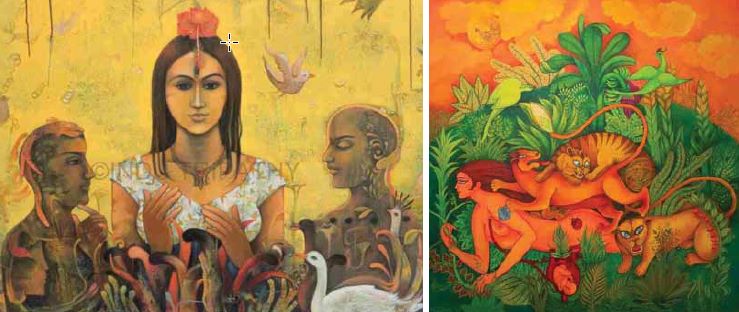

If nature is the macrocosm, the body is the microcosm. Nature is life oriented, while the mind is individual-oriented. When there is a clash between the mind and nature, we try to shape the world following the mind, rather than living in harmony with higher existence. This is where the conflict begins. Nature ultimately wins by reclaiming the bodily form. The balance between the mind and nature has a significant bearing on our ecosystem. The mind uses the body in a way that may or may not be in tune with nature. Nature is not some distant phenomena. In the form of our body, we carry a drop of nature wherever we go. Padmashri awardee Shyam Sharma’s artworks are a fine example of nature entwining with mind. He is one of the greatest living legends India has and is presently based in Patna.

If nature is the macrocosm, the body is the microcosm. Nature is life oriented, while the mind is individual-oriented. When there is a clash between the mind and nature, we try to shape the world following the mind, rather than living in harmony with higher existence. This is where the conflict begins. Nature ultimately wins by reclaiming the bodily form. The balance between the mind and nature has a significant bearing on our ecosystem. The mind uses the body in a way that may or may not be in tune with nature. Nature is not some distant phenomena. In the form of our body, we carry a drop of nature wherever we go. Padmashri awardee Shyam Sharma’s artworks are a fine example of nature entwining with mind. He is one of the greatest living legends India has and is presently based in Patna.

The details of the 16 participating artists:

The details of the 16 participating artists:

" >

" >