Every house in the Odisha village of Raghurajpur is a museum

of art and each household has at least one Chitrakar, who is

highly skilled and immensely creative

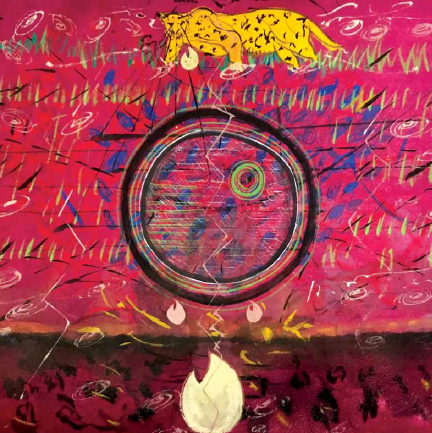

If you ever happen to be in Puri, or Konark, or nearby, you must visit the heritage crafts village of Raghurajpur situated on the banks of river Bhargabi, in Odisha. Located around 12 km from Puri, the coconut and palm-shaded village is home to around 500 chitrakars, who are experts in Pattachitra painting, an art form which dates back to 5 BC. Prime Minister Narendra Modi gifted French President François Hollande a pattachitra (a cloth-based scroll painting) made in Raghurajpur on silk titled Tree of Life reflecting the societal respect for nature in India on his maiden visit to France in 2015. Before Rath Yatra every year, the deities of Puri’s Jagannath Temple go on a 15-day sabbatical. During this period, a pattachitra – an ancient form of painting made on a ‘treated’ piece of cotton cloth using natural colours – takes the place of the original wooden idols. For generations, this pattachitra has been drawn by artists from the nearby village of Raghurajpur. Every year, during Debasnana Purnima, which marks the onset of one of the biggest festivals in Odisha — the Ratha Jatra — the trinity deities Lord Jagannath, Lord Balabhadra and Devi Subhadra take a bath with 108 pots of cold water to fight the heat of summer. After this, the deities supposedly fall sick for a period of 15 days known as ‘anasara’. During this 15- day period, the deities are absent from public view and pattachitra of the deities made by, chitrakars of Raghurajpur is placed in the Puri Jagannath Temple for the people to pay obeisance.

During this 15-day period of anasara, the deities are absent

from public view and pattachitra of the deities made by

chitrakars of Raghurajpur is placed in the Puri Jagannath

Temple for the people to pay obeisance.

Every house in this Odisha village is a studio and each household has at least one Chitrakar who is highly skilled and immensely creative. Along Raghurajpur’s two streets, amid coconut groves, there are over 100 homes covered in colourful murals — each a museum of art. Apart from pattachitra and palm leaf paintings, you will find artists making papier-mâché toys, masks, coconut crafts, wooden toys, etc. Each family has a distinct style of painting and the craft is passed down through generations. Most children who are 10-11 years old are taught the ancient art form, which their ancestors had been practising for generations. “I have been making pattachitra and palm leaf engravings for the past 35 years. It is my hereditary work, which I have also taught my children. They may not be as fine artisans as the older generation, but will hopefully keep our traditional art form alive,” says Avinash Nayak, who started learning the art when he was just 12.

Apart from the need to introduce synthetic colours, the art has remained unchanged. With art-loving travellers seeking out the craft, artists are replacing traditional long scrolls — that can sometimes be a few feet long — with smaller versions that can be framed in urban homes as souvenirs. The themes of the paintings remain true to their roots, featuring most popularly, the triad of Puri, followed by Lord Krishna. Paintings of the Dasavatars and the Dasa Mahavidyas are also common, as are scenes from mythological texts and stories. In the case of palm leaf engraving, palm leaves (commonly known as talapatra), sourced locally, are used and carved with needles or iron stylus to narrate a story. Pothichitra is a type of palm leaf engraving, which is in the shape of a pothi (book) and has both chitra and words written on it to narrate a story. Even as the village basks in its recent national and international glory, old-timers recall the efforts of Halina Zealey, an American researcher, and their very own Jagannath Mohapatra (winner of President of India’s award in 1965) to create a studio in every household. The village, about 50 km from Bhubaneswar, was initially home to five to six chitrakar families. The fortunes of these artists dwindled at the beginning of the 20th century with the entry of middlemen. Till then, they created pattis for the Lord Jagannath Temple and also sold these at the Bedha Mahal. By the 1950s, only a few old men continued painting. “In 1952, Halina Zealey organised a competition where artists from nearby villages participated. Mohapatra impressed her with a painting on Matsya Avatar (a fish incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu). But by then, most artists of Raghurajpur had turned labourers who supplied water to betel vines. Mohapatra eked out a living by working as a mason. When the neighbouring Dandasahi villagers joked about it, an aggrieved Mohapatra decided to create an artist in every home,” says Bhagawan Swain of Parampara, an NGO that coordinates the ground-level entrepreneurs of the village. Swain says Zealey understood the need to promote these products to sustain the art form. “She set up Banijya Vikas Kendra in Puri. Before leaving Odisha in 1954, she gave Mohapatra revolving fund to support the cause,” he added. Lakshmidhar Subudi, a Kala Puraskar awardee for his Thalachitra (carving done on palm leaves and filling it with black colour) for his art of Krishna Leela, says,”These days the art form has got commercialised. The artists have adapted to the modern society and their needs. They paint things the customer wants. Ultimately it is the struggle for bread and butter.”

In fact, the region is also home to the beautiful art form Gotipua, precursor to the Indian classical dance form of Odissi. It has been performed in Odisha for centuries by young boys, who dress up as women to praise Lord Jagannath and Lord Krishna. The dance is executed by a group of boys who perform acrobatic figures inspired by the life of Radha and Krishna. The dance form is a mixture of Odissi classical dance and Mahari style (which was once devoted by Devadasis, to Lord Jagannath). Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, the much-awarded exponent of Odissi dance, was born in Raghurajpur. In his youth, he performed Gotipua. Later in his life, he did extensive research on Gotipua and Mahari style, which led him to restructure Odissi dance. He was the first to be awarded Padma Vibhushan from Odisha. At the far end of the village, stand two organisations that have been nurturing Gotipua with all its pristine flavour and glory—Dasabhuja Gotipua Odissi Nrutya Parishad and Abhinna Sundar Gotipua Nrutya Parishad.Dasabhuja Gotipua Odishi Nrutya Parisad was established in 1977 by Guru Maguni Charan Das, a Padma Shri awardee and recipient of Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi award, and the dance school has played a lead role in the revival of the form. Sebendra Das, brother of Guru Maguni Das, currently runs the Dasabhuja Parishad. He explains the relevance of the dance form. “Gotipua is an amalgamation of two Odia words; Goti means single and Pua means boy. When the dance of the Maharis and the Devadasis of the Jagannath Temple at Puri disintegrated due to various reasons, young boys from various ‘akhadas’ were trained to take the tradition forward. Earlier, Gotipua used to be performed by a single boy, but over the years it evolved as a group dance.” Late Guru Laxman Maharana set up Abhinna Sundar Gotipua Nrutya Parishad, which has been working for the promotion and popularisation of the ancient dance form for 19 years. In 2000, Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) declared Raghurajpur a ‘heritage village’, which has helped the artists explore other traditional art forms as well. Near to Raghurajpur is another village named Dandasahi, which has the potential of becoming a heritage village of tomorrow. A small village of about 50 households, Dandasahi is on the side of the historical road, through which Sri Chaitanya had travelled to Puri.

" >

" >

" >

" >